From Cape Town to Cairo, Bahia to Bombay, recent calls to "decolonise the university" have gained traction across the globe. These demands correctly challenge the legacies of colonialism and attempt to subvert them in institutional structures of higher learning.

But the problem with this 21st-century "scholarly decolonial turn" is that it remains largely detached from the day-to-day dilemmas of people in formerly colonised spaces and places. Many academics mistakenly maintain that by screaming "decolonise X" or "decolonise Y" ad nauseam, they will miraculously metamorphose into progressive agents of change.

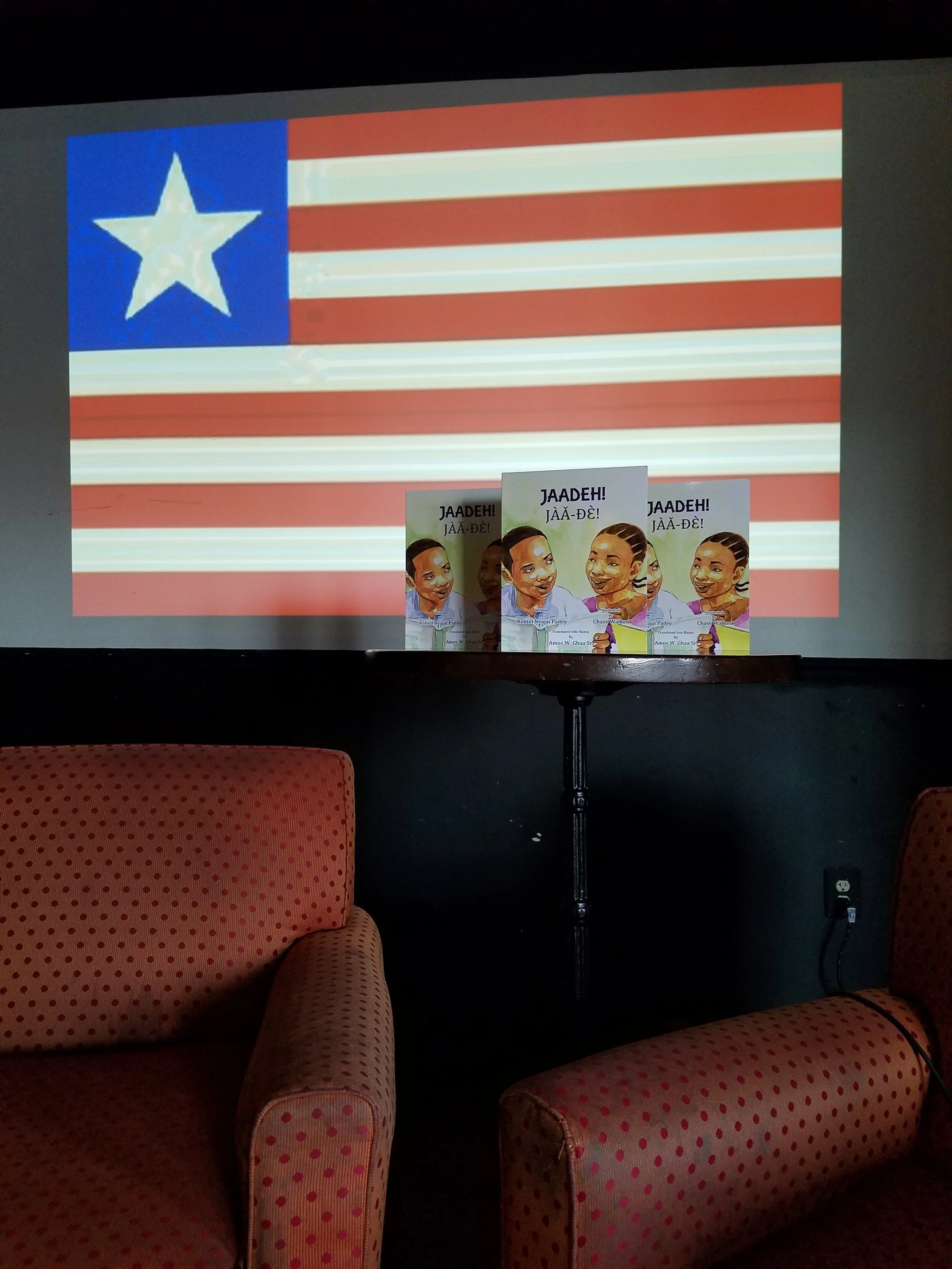

Some tragically believe that by ignoring leading thinkers who were "decolonising" long before it became a fad - including Edward Wilmot Blyden of Liberia and WEB DuBois of the US who were prominent as early as the mid-to-late 1800s - they can carve out "decolonisation" as their scholarly fiefdoms.

Still others erroneously contend that "decolonial" street credibility can be acquired by simply adding non-whites to their reading lists, journal editorial boards, speaking panels, research collaborations, book contracts, etc.

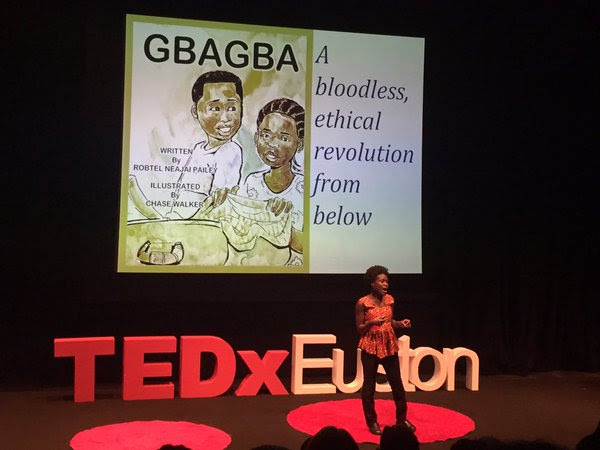

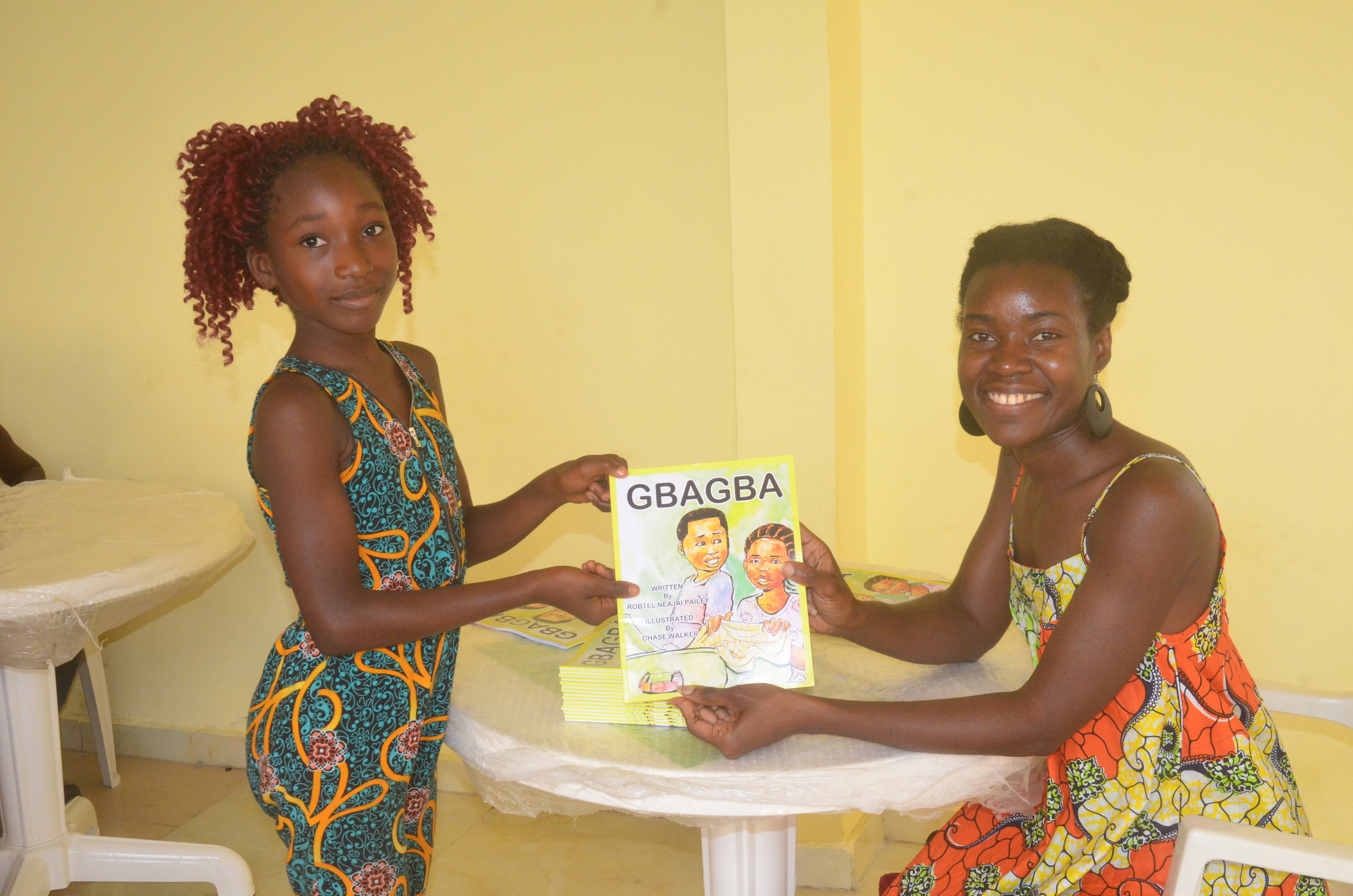

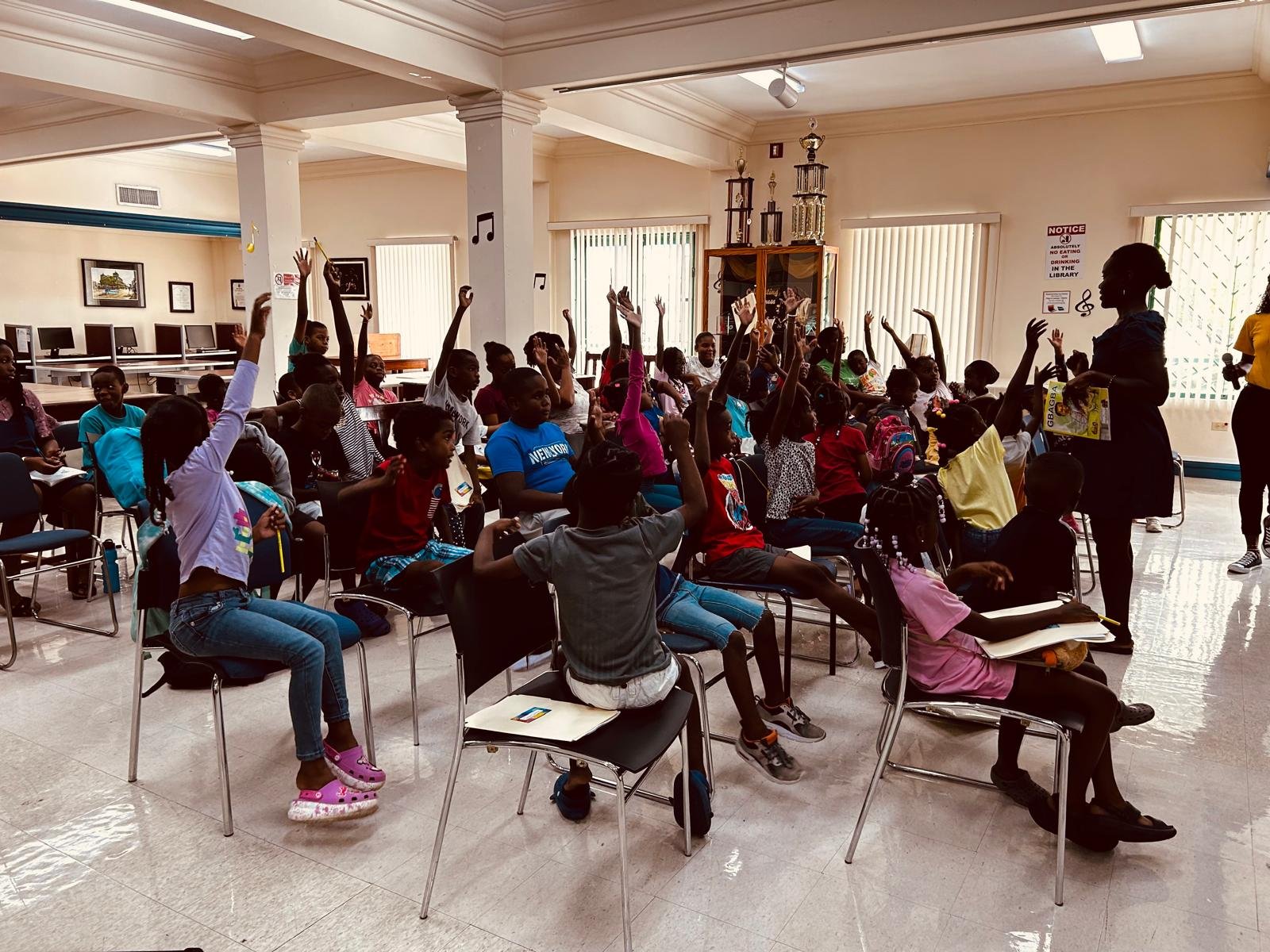

Despite these flawed assumptions, 21st-century "epistemic decolonisation" cannot succeed unless it is bound to and supportive of contemporary liberation struggles against inequality, racism, austerity, patriarchy, autocracy, homophobia, xenophobia, ecological damage, militarisation, impunity, corruption, media muzzling and land grabbing.

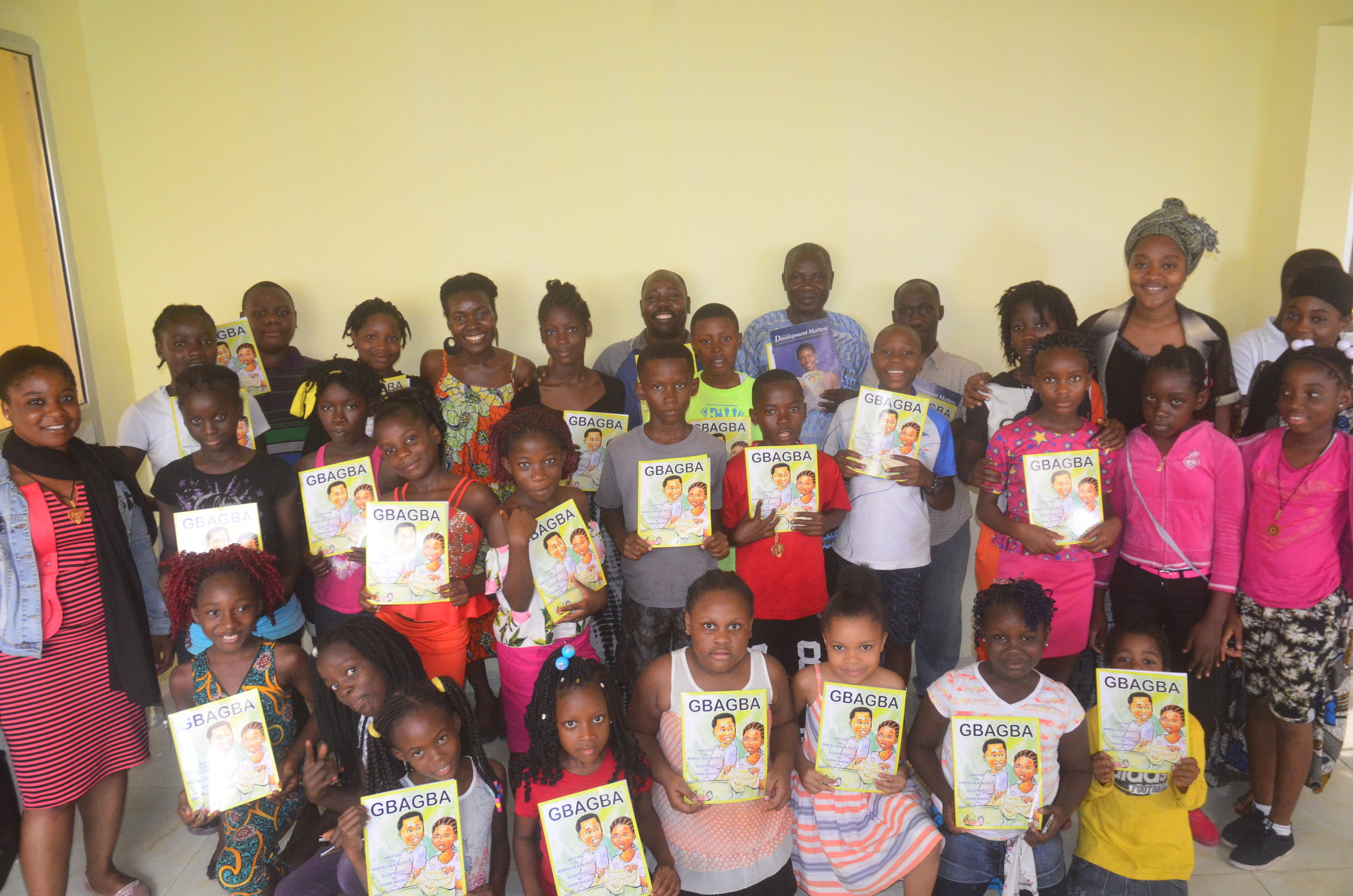

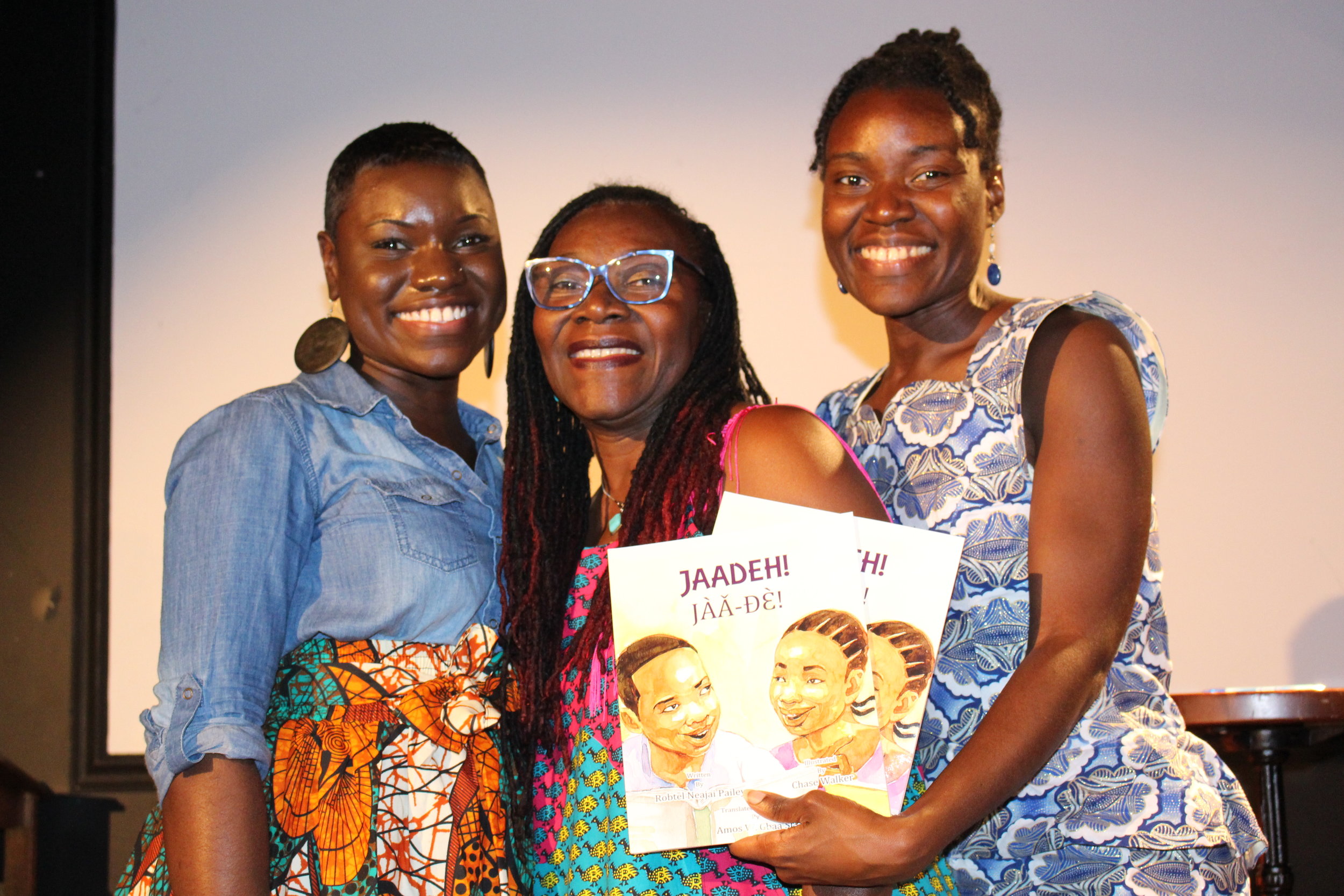

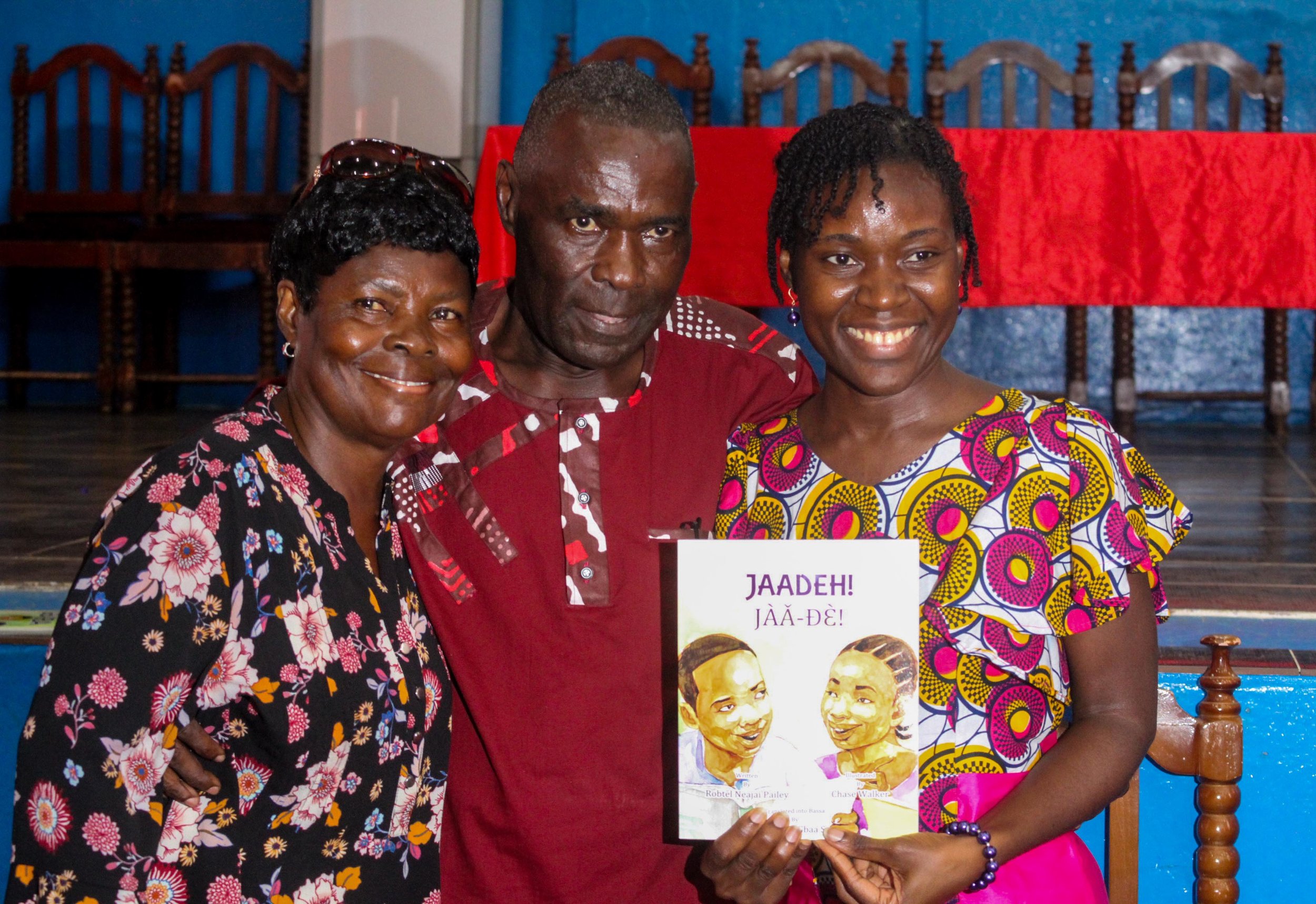

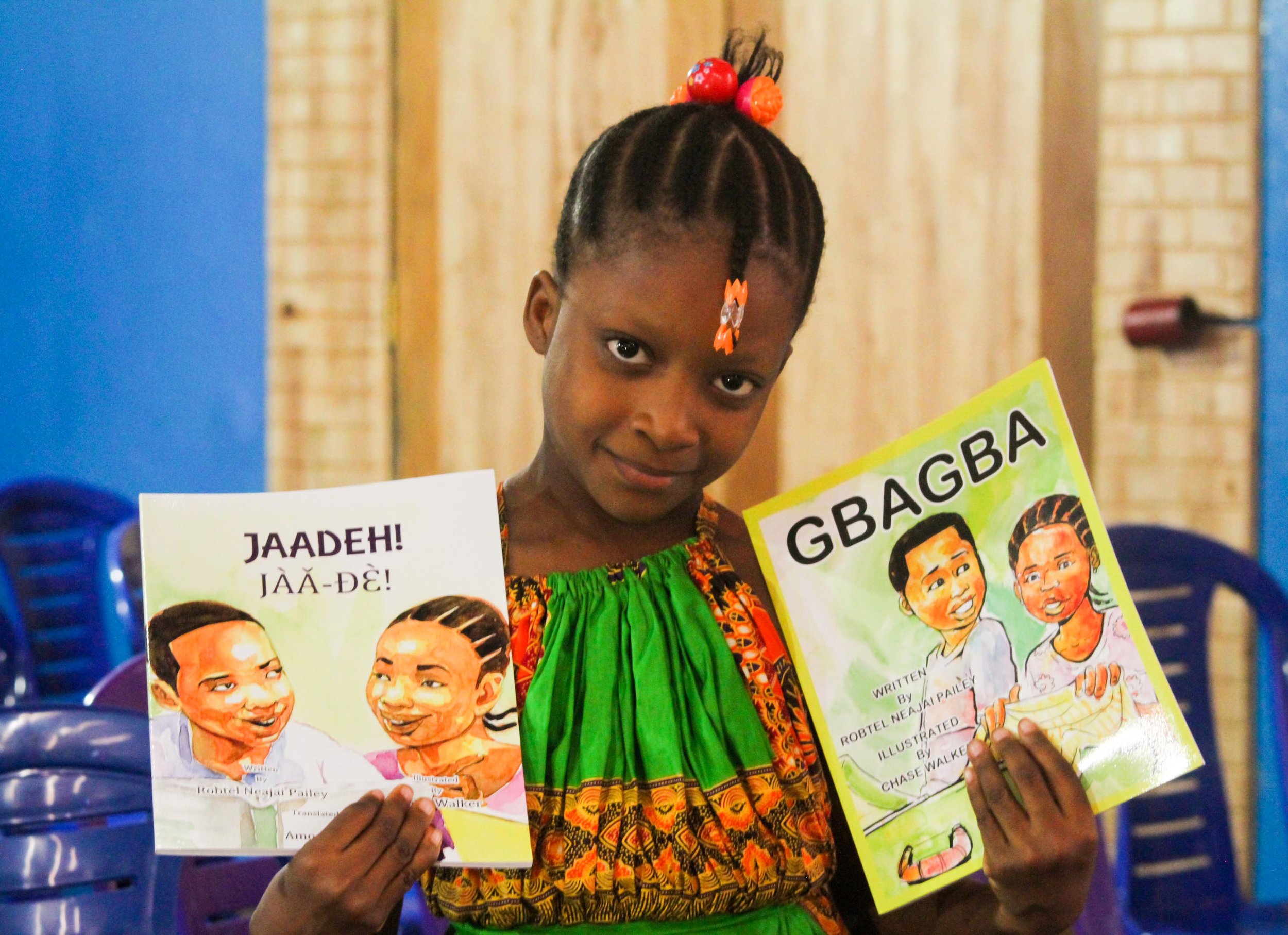

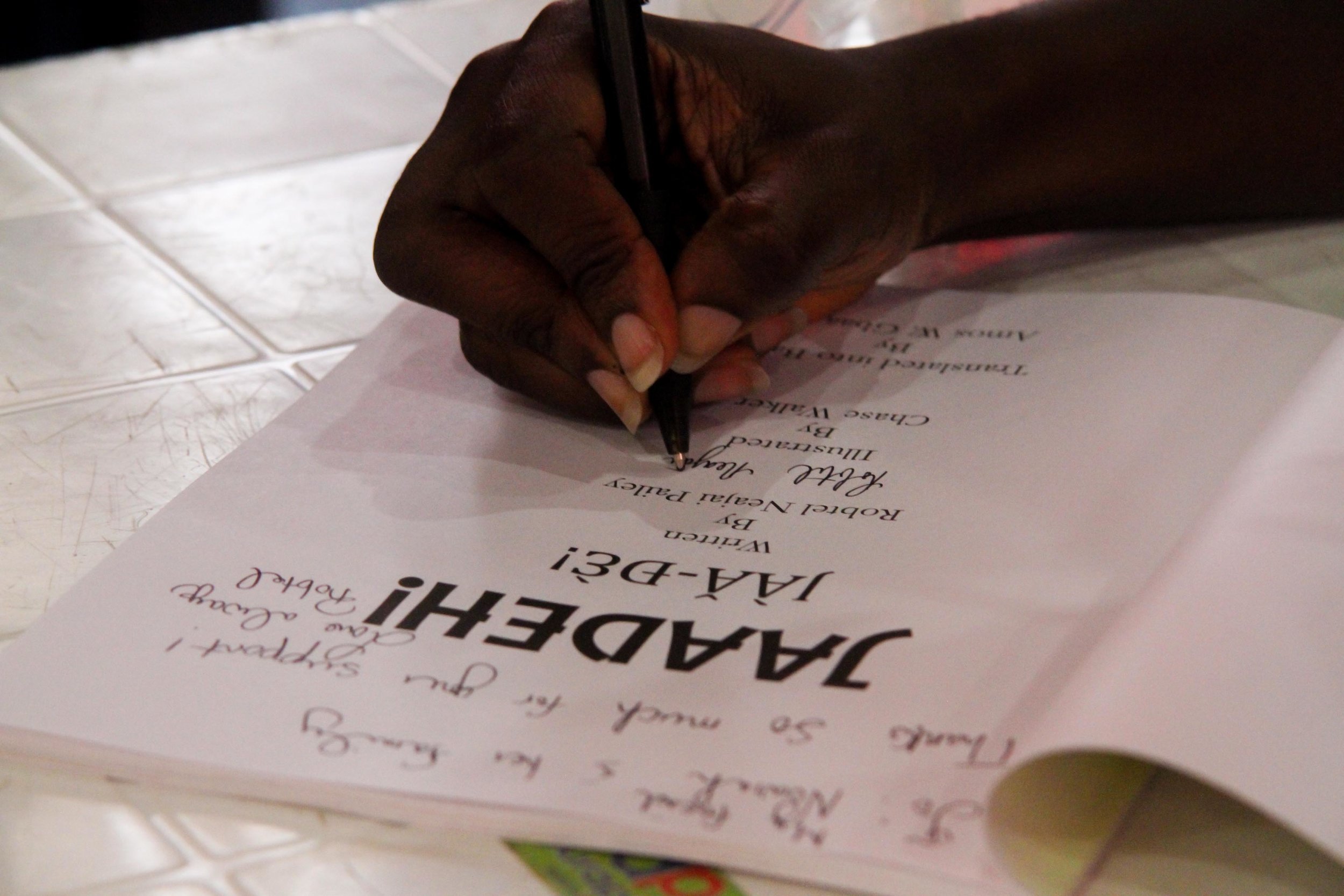

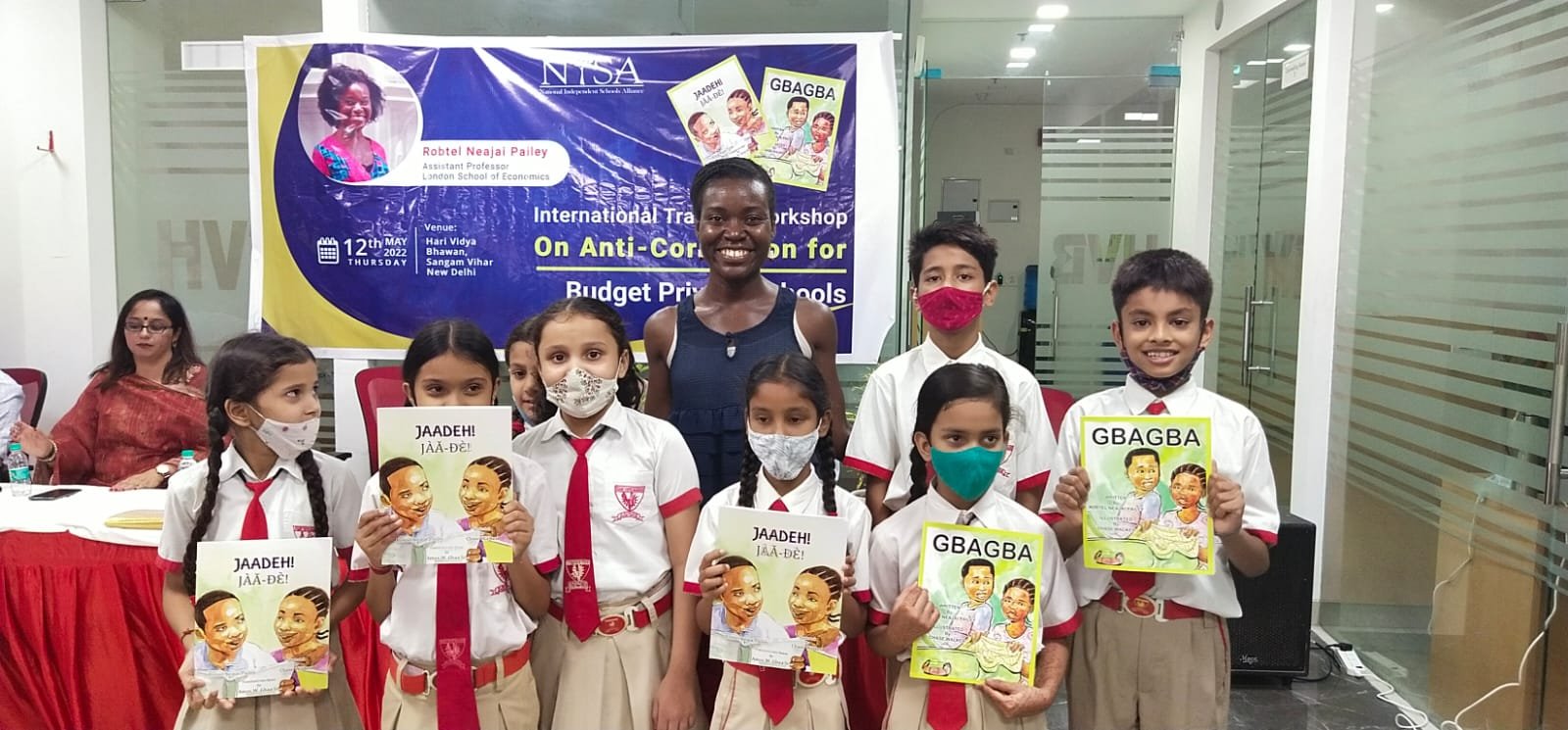

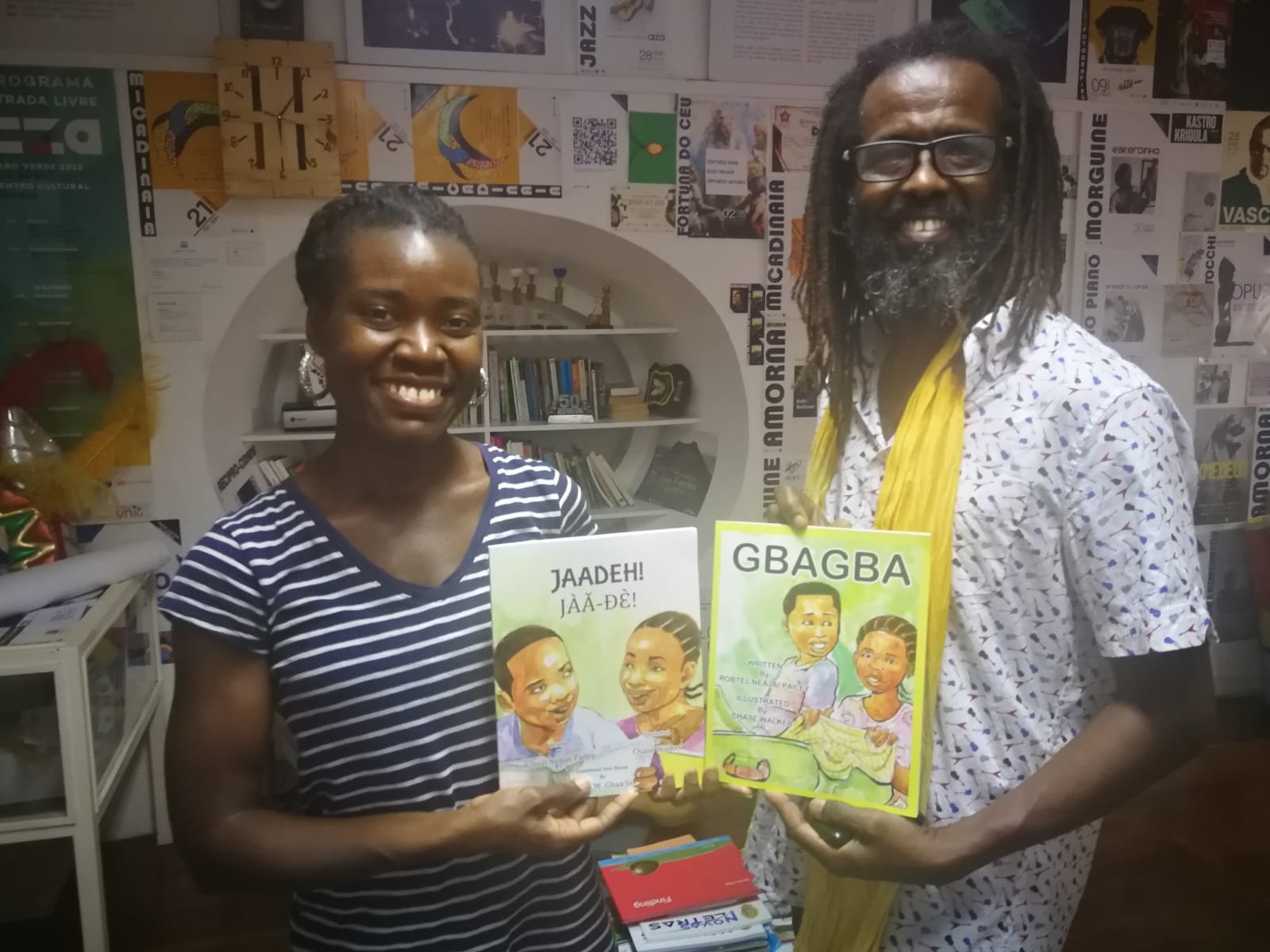

For those who research and write about Africa, this is particularly important given the continent's fraught relationship with itself and the outside world. Though Africa remains captured today by the same forces that fuelled colonialism, African activists and artists have responded by commanding revolutionary change.