I feel like an imposter. Out of place and exposed.

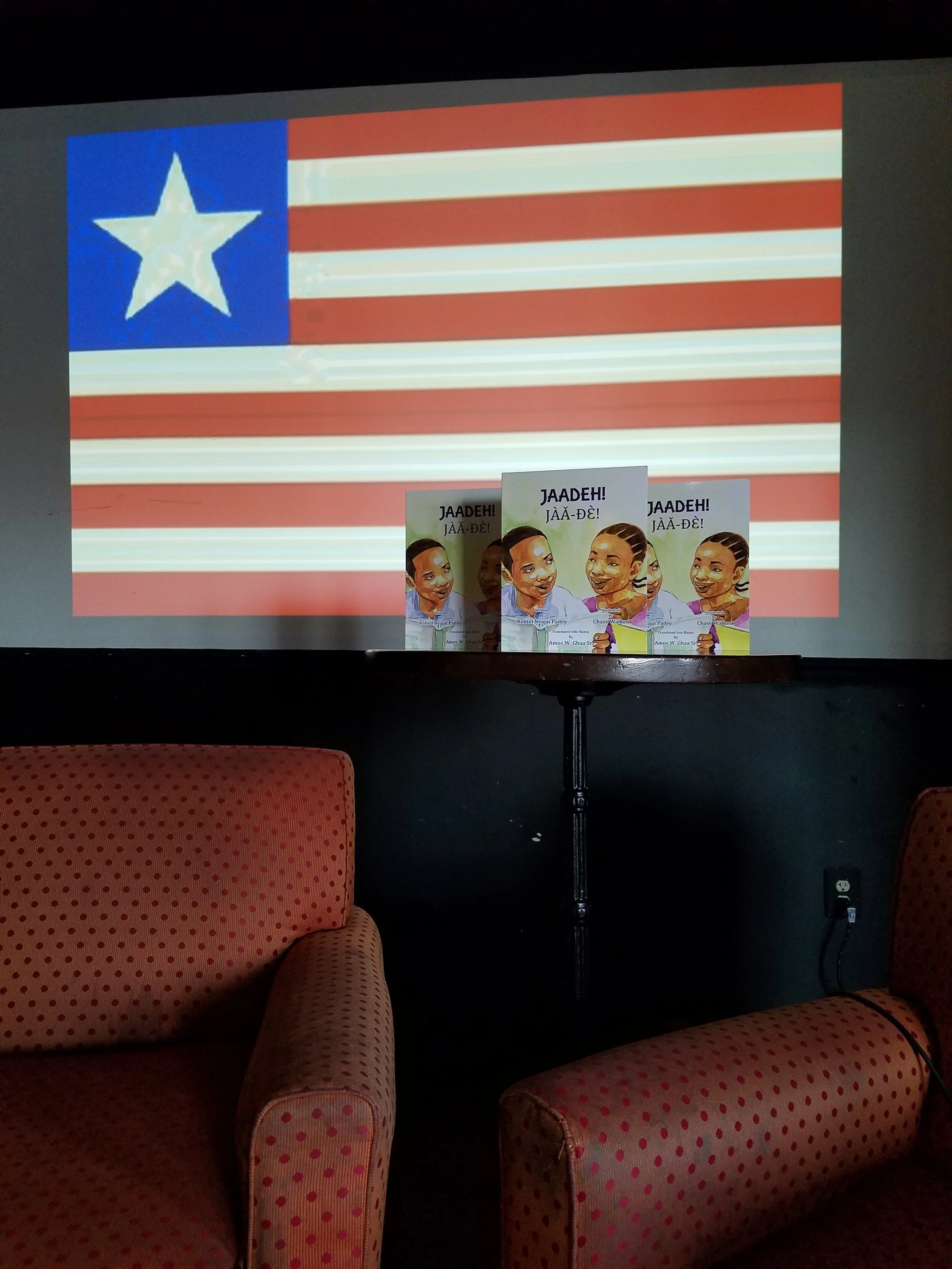

Monsoon-like rains have subsided and the dry season air is thick and balmy in Monrovia, Liberia. It is circa October 2007. I am 25 and ‘home’ for the first extended period of time since international headlines stopped calling our country’s 14-year armed conflict ‘brutal’ and ‘grotesque’. Since our former head-of-state-turned-regional-warmonger was exiled.

During an earlier Christmas-season visit in 2002, I embrace this land of my birth, its people and their idiosyncrasies with a fierceness that throbs. It is the first of first returns since leaving, aged six, to join Mom and Dad in Washington, DC. There is a lull in the heavy fighting but I can count on fingers and toes war-era checkpoints that partition the bumpy Roberts International Airport road, a two-lane winding expanse surrounded by lush forest.

I marvel at daylight tours of our shell-shocked capital city and its suburbs, of bullet-ridden concrete fences, sprawling estates, open-air markets, beaches that beckon. Some of the sites unlock blissful memories of my tree-climbing and Knockfoot-playing girlhood. Others reveal visible and psychic wounds, like the crumbling edifice of a maternal uncle’s home, or the gaping hole left by a paternal grandfather whose disappearance at sea in the 1960s we attribute to the occult.

Under a star-lit sky, I greedily gulp down family tragedies and triumphs narrated late into the night. These are fevered attempts to fill in the gaps of lives separated by time, space and place. By war and peace.

Violence, of both the physical and structural kind, has numbed our senses. This leaves me circumspect. Macro-level talk is too dicey, so I try to speak solely about the familiar and familial. While Mom has given her blessing for me to be here on the condition that I keep all political views to myself, Dad is more supportive of my need to wrestle with our complicated country. He does not begrudge me for squandering all my savings on a roundtrip flight from Accra to Monrovia, purchased before notifying both parents because I know they will disapprove. A four-month stint studying at the University of Ghana becomes the perfect decoy for plotting my prodigal return home, and Dad admits that he considers my actions plucky.

Yet, despite a steely facade, I am far from brave five years later. My wishbone-shaped legs wobble in black mini-pumps—a parting gift from my mother—as they emit a shiny glow of newness. Though quick to shrug off others’ opinions of me, more out of insecurity than confidence, I know that we Liberians have mastered the art of judging a book by its cover. The content of one’s character is of less significance, so my mother spends much of my childhood, adolescence and young adulthood playing ‘respectability police’. She tries to exorcise my wilfulness, inherited from a lineage of Kru warriors who once battled black migrant settlers attempting to carve out a ‘land of liberty’, now Liberia, that did not belong to them. Back then, I resisted Mom’s impulse to shield me from razor-sharp scrutiny that is gendered, aged and classed.

Her armour of protection now gone, I feel naked. In an effort to smooth out any seemingly rough edges, lest I be harangued for them, I twist my shoulder-length dreadlocks with dark-brown tips tighter than usual at the roots.